In State v. Tarango, the WA Court of Appeals held that the presence of a firearm in public and the presence of an individual openly carrying a handgun in a “high-risk setting,” are insufficient, standing alone, to support an investigatory stop.

BACKGROUND FACTS

At around 2:00 in the afternoon on a winter day in 2016, Mr. Matthews drove to a neighborhood grocery store in Spokane, parking his car next to a Chevrolet Suburban in which music was playing loudly. A man was sitting in the passenger seat of the Suburban, next to its female driver. When Mr. Matthews stepped out of his car and got a better look at the passenger, who later turned out to be the defendant Mr. Tarango, he noticed that Mr. Tarango was holding a gun in his right hand, resting it on his thigh. Mr. Matthews would later describe it as a semiautomatic, Glock-style gun.

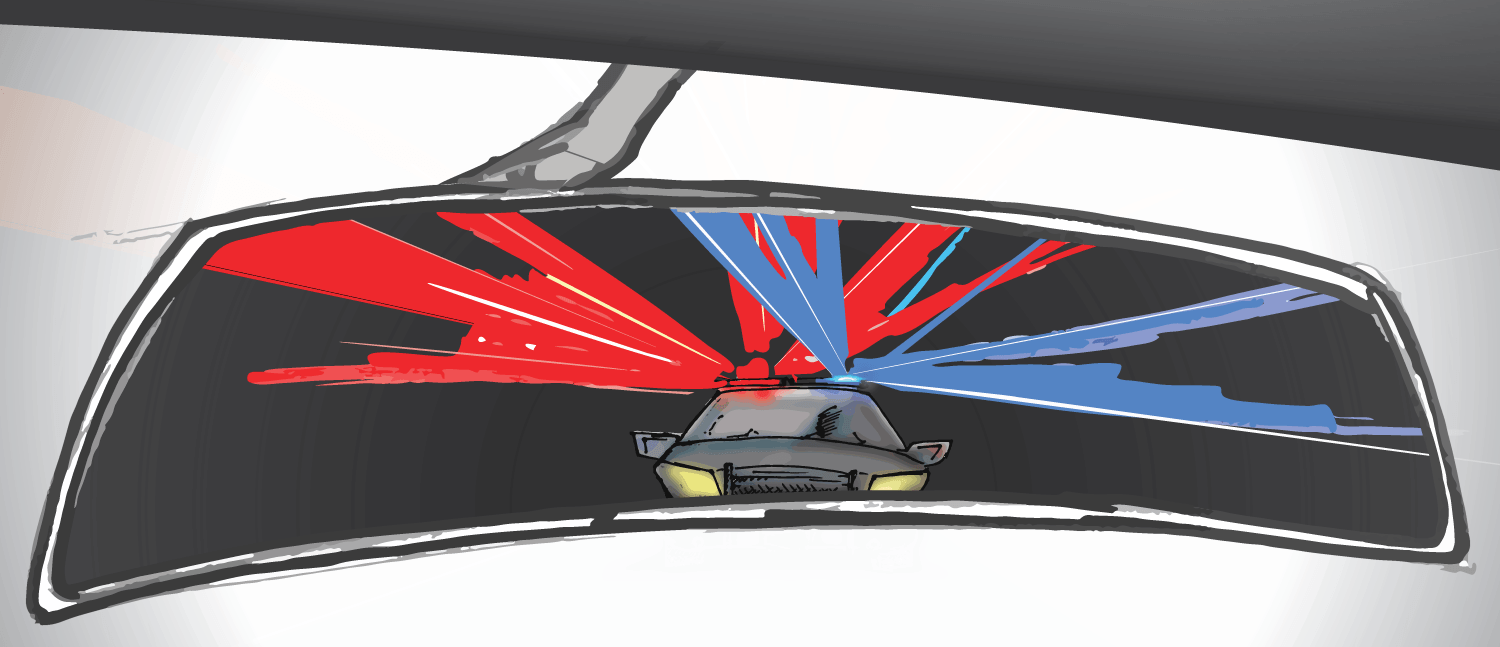

As he headed into the store, Mr. Matthews called 911 to report what he had seen, providing the 911 operator with his name and telephone number. The first officer to respond saw a vehicle meeting Mr. Matthews’s description parked on the east side of the store. He called in the license plate number and waited for backup to arrive. Before other officers could arrive, however, the Suburban left the parking area, traveling west.

The Suburban was followed by an officer and once several other officers reached the vicinity, they conducted a felony stop. According to one of the officers, the driver, Lacey Hutchinson, claimed to be the vehicle’s owner. When told why she had been pulled over, she denied having firearms in the vehicle and gave consent to search it.

After officers obtained Mr. Tarango’s identification, however, they realized he was under Department of Corrections (DOC) supervision and decided to call DOC officers to perform the search.

In searching the area within reach of where Mr. Tarango had been seated, a DOC officer observed what appeared to be the grip of a firearm located behind the passenger seat, covered by a canvas bag. When the officer moved the bag to get a better view of the visible firearm—the visible firearm turned out to be a black semiautomatic—a second firearm, a revolver, fell out. Moving the bag also revealed a couple of boxes of ammunition. At that point, officers decided to terminate the search, seal the vehicle, and obtain a search warrant. A loaded Glock Model 22 and a Colt Frontier Scout revolver were recovered when the vehicle was later searched.

The State charged Mr. Tarango, who had prior felony convictions, with two counts of first degree unlawful possession of a firearm. Because Mr. Tarango had recently failed to report to his community custody officer as ordered, he was also charged with Escape from community custody.

Before trial, Mr. Tarango moved to suppress evidence obtained as a result of the traffic stop, arguing that police lacked reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. However, the trial court denied the suppression motion. Later, at trial, the jury found Mr. Tarango guilty as charged. He appealed.

ISSUE

The issue on appeal was whether a reliable informant’s tip that Mr. Tarango was seen openly holding a handgun while seated in a vehicle in a grocery store parking lot was a sufficient basis, without more, for conducting a Terry stop of the vehicle after it left the lot.

COURT’S ANALYSIS & CONCLUSIONS

First, the Court of Appeals held that Mr. Tarango’s motion to suppress should have been granted because officers lacked reasonable suspicion that Mr. Tarango had engaged in or was about to engage in criminal activity.

The Court reasoned that warrantless searches and seizures are per se unreasonable unless one of the few jealously and carefully drawn exceptions to the warrant requirement applies.

“A Terry investigative stop is a well-established exception,” said the Court. “The purpose of a Terry stop is to allow the police to make an intermediate response to a situation for which there is no probable cause to arrest but which calls for further investigation . . . To conduct a valid Terry stop, an officer must have reasonable suspicion of criminal activity based on specific and articulable facts known to the officer at the inception of the stop.”

Additionally, the Court of Appeals reasoned that in evaluating whether the circumstances supported a reasonable suspicion of criminal conduct, it reminded that Washington is an “open carry” state, meaning that it is legal in Washington to carry an unconcealed firearm unless the circumstances manifest an intent to intimidate another or warrant alarm for the safety of other persons.

“Since openly carrying a handgun is not only not unlawful, but is an individual right protected by the federal and state constitutions, it defies reason to contend that it can be the basis, without more, for an investigative stop.”

Here, because the officers conducting the Terry stop of the Suburban had no information that Mr. Tarango had engaged in or was about to engage in criminal activity, the officers lacked reasonable suspicion.

Consequently, the Court of Appeals ruled that Tarango’s motion to suppress should have been granted. The Court also reversed and dismissed his firearm possession convictions.

Please contact my office if you, a friend or family member are charged with a crime. Hiring an effective and competent defense attorney is the first and best step toward justice.