Excellent article from the Sentencing Project describes how voters in a number of states considered ballot measures during yesterday’s Midterm Election. Criminal justice reform measures ranged from voting rights to sentencing reform.

Colorado – Abolishing Involuntary Servitude as Punishment

Coloradans approved Amendment A with 65% support; the measure removes language from the state Constitution that allows slavery and involuntary servitude to be used as punishment for the conviction of a crime. Abolish Slavery Colorado organized a broad coalition in support of the constitutional change. Supporters included faith groups and civil rights organizations.

Florida – Expanding the Vote

State residents expanded voting rights to as many as 1.4 million Floridians with a felony conviction by approving Amendment 4 with 64% support; support from 60% of voters was required to approve the ballot measure. Justice involved residents now automatically have the right to vote once they complete their prison, probation or parole sentence; persons convicted of homicide and sex offenses are excluded from the measure.

The state’s lifetime felony voting ban was among the most restrictive in the country, along with Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia which maintain lifetime voting bans for all felonies unless the governor takes action. The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which organized broad support for the measure, was led by directly impacted residents and garnered more than 800,000 signatures to qualify Amendment 4 for the ballot.

Florida – Retroactivity & Sentencing

Also in Florida, voters approved Amendment 11 with 62% support, a measure that allows sentencing reforms to be retroactive. The amendment repeals language from the state’s ‘Savings Clause’ in the constitution that blocks the legislature from retroactively applying reductions in criminal penalties to those previously sentenced. Statutory law changes are not automatically retroactive; the legislature still has to authorize retroactivity for a particular sentencing reform measure.

Louisiana – Requiring Unanimous Jury Consideration

Louisianans approved Amendment 2, a constitutional change requiring unanimous juries for all felony convictions. In all other states, except Oregon, a unanimous jury vote is required to convict people for serious crimes; Louisiana was the only state where a person could be convicted of murder without a unanimous jury. Advocacy for Amendment 2 was supported by a broad coalition that advanced criminal justice reforms in recent years. The state’s Democratic and Republican parties endorsed Amendment 2, as well as community groups including Voice of the Experienced, and Americans for Prosperity.

Michigan – Authorized Marijuana Possession

Michiganders approved Proposal 1, a measure that legalizes marijuana for adult recreational use. The change means residents over age 21 will be able to possess up to 2.5 ounces of marijuana on their person and up to 10 ounces in their home. The newly elected governor has signaled support to pardon justice involved residents with prior marijuana convictions and legislation is pending to require judges to expunge misdemeanor marijuana convictions.

Ohio – Rejected Felony Reclassification Measure

Ohio residents rejected Issue 1, a measure that would have reclassified certain drug offenses as misdemeanors and prohibited incarceration for a first and second offense. The measure failed with 65% voting against the sentencing reform. In recent years, voters in California and Oklahoma approved similar ballot initiatives to reclassify certain felonies as misdemeanors with a goal of state prison population reduction.

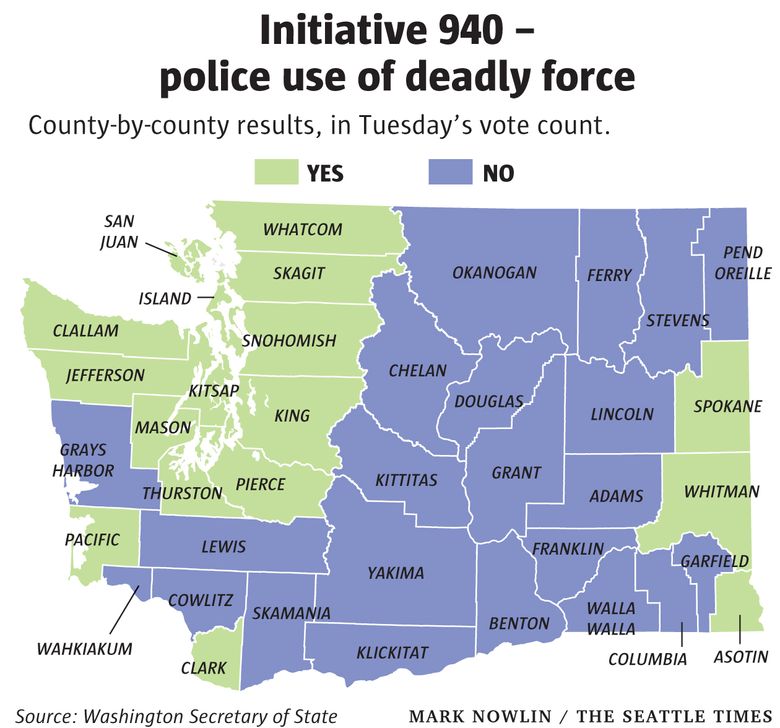

Washington – Strengthening Police Accountability

Voters passed Initiative 940 and repealed a provision in state law that made it difficult to bring criminal charges against police for deadly force. The Washington law required prosecutors to prove “evil intent” or “malice” when filing charges like manslaughter against police officers. Washingtonians approved the measure with 60% support. I-940 also requires training in de-escalation and mental health for law enforcement officers; requires police to provide first aid to victims of deadly force; and requires independent investigations into the use of deadly force.

My opinion? State initiatives provide an opportunity to civically engage communities on criminal justice policies and build momentum to challenge mass incarceration.

Midterm voters across the nation have spoken. For the most part, their decisions are a step in the right direction. We see an end to involuntary servitude in prison, granting voting rights to some convicted felons, jury unanimity, the legalization of marijuana and the strengthening of police accountability. Good.

Please contact my office if you, a friend or family member are charged with a crime. Hiring an effective and competent defense attorney is the first and best step toward justice.